Activists in Australia are trying to stop oil and gas company Woodside Energy from conducting seismic blasting off the country’s western coast, which they say could deafen and ultimately kill endangered migratory whales.

The court challenge is part of a long-running campaign by Indigenous and environmental activists to frustrate Woodside’s plans for “Scarborough,” a massive fossil fuel project set to pump out carbon emissions for decades even as Australia attempts to meet tougher climate targets.

Earlier this month, Marthudunera woman Raelene Cooper sought an injunction to delay the blasting, but that order is due to expire on Thursday, allowing Woodside to resume work it says is required to indicate the location of large gas reserves.

On Tuesday, Cooper argued her case in the Federal Court, saying she was not properly consulted by Woodside Energy before it announced the blasting, a precursor to exploratory drilling.

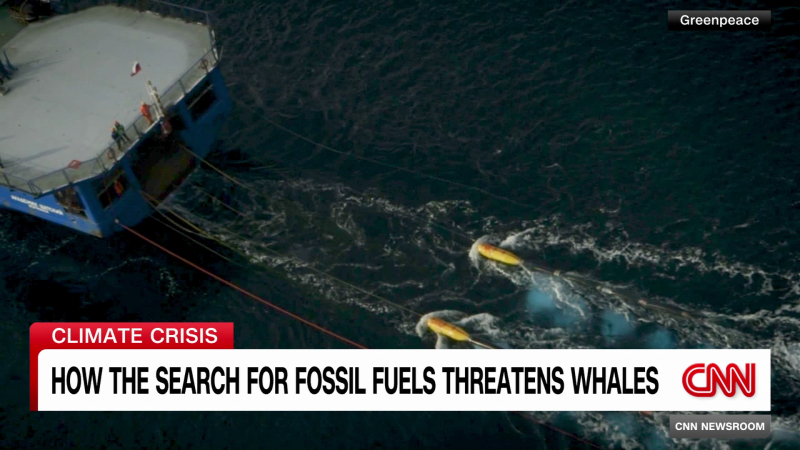

During the process, airguns fire compressed air toward the ocean floor and the soundwaves penetrate the seabed before bouncing back to receivers towed by a boat. The pattern of the soundwaves gives geologists an indication of oil and gas reserves trapped under the ocean bedrock.

According to the Australian Marine Conservation Society, the noise can reach 250 decibels, around a million times “more intense” than the loudest whale sounds.

“Now, that’s really problematic if you’re a whale because whales depend on their hearing for everything – to navigate, to find their mates and their food,” said Richard George, Greenpeace Australia Pacific senior campaigner.

“So, a deaf whale is a dead whale.”

Huge gas project

Woodside Energy plans to extract millions of tons of gas from the Scarborough field, about 375 kilometers (233 miles) off the coast of Western Australia, mostly for export to Asia.

The project was signed off by the previous Australian government led by Scott Morrison, however it retains the support of Prime Minister Anthony Albanese’s administration, despite its pledge of achieving net zero emissions by 2050.

Gas is generally less carbon-intensive than coal, but it’s still a planet-warming fossil fuel, and there is a growing understanding that its infrastructure leaks huge amounts of methane – a more potent greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide in the shorter term.

Australia’s offshore oil and gas regulator, NOPSEMA, approved the blasting in July, despite acknowledging that Woodside may not have identified all Indigenous people in need of consultation on the seismic blasting plans, or given them adequate time to be consulted.

The document lists dozens of threatened and migratory species of sharks, mammals, reptiles and birds that can be found in the vicinity of the blast zone, including loggerhead and leatherback turtles, great white sharks and pygmy blue whales.

Greenpeace said Woodside’s plans “skirt close” to a major migration route for pygmy blue whales, a smaller subspecies of blue whale that travels north each year from the Antarctic into waters off Australia’s northwest.

The population size of pygmy blue whales is unclear, but the Australian government considers the mammal to be endangered.

The government’s species profile warns about the dangers of “man-made noise” to the whales, saying it can “potentially result in injury or death, masking of vocalisations, displacement from essential resources (e.g. prey, breeding habitat), and behavioural responses.”

“Potential sources of man-made underwater noise interference in Australian waters include seismic surveys for oil, gas and geophysical exploration,” the profile adds.

However in its environmental report, Woodside said any impact on whales would be short term.

“There will be no lasting effect on whales, however there could be short term hearing impacts,” Woodside wrote in its report.

The company also said it “will have dedicated marine fauna observers and systems which can listen for whale song on some vessels” and that the “presence of whales can postpone activities.”

Fight for cultural heritage

For local Indigenous people, whales are not only treasured for their role in the ecosystem – they carry cultural significance for those whose ancestors have lived on the land for more than 60,000 years.

“It’s what our ancestors left behind, they left us a story,” Cooper said. “Those animals represent a song, a dance that we as Indigenous people all over this continent hold.”

In its environmental plan, Woodside acknowledged the importance of marine habitats to the traditional customs and culture of Indigenous Australians.

“Woodside recognises the potential for marine ecosystems to include cultural features as well as environmental values,” the report said. “An impact to marine ecosystems has the potential to impact cultural values,” Woodside acknowledges, vowing to “adequately manage” that impact.

But the activists’ concerns extend beyond the sea – to ancient petroglyphs or rock art on Murujuga, also known as Burrup Peninsula, that Cooper and her group, Save our Songlines, fear will be damaged by emissions from the Scarborough project.

The art, believed to be 40,000 years old, contains some of the earliest depictions of human civilization and represent irreplaceable cultural links to the past.

“It’s our sacred significant areas that are continually getting hammered,” she said. “Our people are being attacked. Our ancient history, our wildlife, our ecosystems, our water.”

Woodside Energy has calculated a total emissions cost of 878.02 megatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent over its 50-year lifespan.

Campaigners say the projected emissions made a mockery of Australia’s stated commitment to reducing its reliance on fossil fuels.

“Scarborough is a part of the Burrup Hub, and that is Australia’s largest fossil fuel project. If it goes ahead we’re looking at emissions equivalent to 12 years of Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions,” said Greenpeace’s Richard George.

“So it is a disaster for our climate and it’s a disaster for our oceans as well.”