It’s one thing standing in line to watch the blockbuster film “Oppenheimer.” It’s another thing entirely queueing up in a remote desert to experience the location of the film’s most pivotal scene.

But if you’re a fan of atomic history and can swing central New Mexico this October, your pilgrimage through the Jornada del Muerto (Dead Man’s Journey) will be so worth the effort.

Saturday, October 21, presents a rare opportunity to visit not just one but two scientifically significant and movie-famous destinations on the same day – each occupying opposite ends of the electromagnetic spectrum.

Trinity Site is the national historic landmark that’s home to mankind’s first nuclear blast on July 16, 1945, where plutonium gamma rays lit up the night sky. It hosts only two open house events each year.

And while you’re in the area, an extraordinary bonus is a second, free-of-charge open house aimed specifically at Trinity Site adventurers who are willing to drive another 100 miles to take in a second mind-bending experience.

It’s the Very Large Array Radio Observatory (VLA), which was dramatized in the 1997 alien-life movie “Contact.” The VLA telescope can spread wider than New York City, able to capture the whispers of distant radio waves as they undulate across our cosmos.

Rare access to Trinity Site

Trinity Site opens only two Saturdays a year. Once in April, and lucky for “Oppenheimer” enthusiasts, again in October.

The exact dates are announced in advance each year by the US Army.

The site is a secure military installation within the forbidding White Sands Missile Range, where live weapons are regularly tested. The terrain is high desert plateau, dotted with creosote brush and not much else.

In our everyday crush of crowds, traffic and strip malls, the Land of Enchantment’s sheer miles of open landscape and soul-nourishing cobalt vistas inspire. Buzz Aldrin’s impression of the moon’s surface parallels Trinity Site, a “magnificent desolation.”

When J. Robert Oppenheimer, the theoretical physicist known as the “father of the atomic bomb,” led his Manhattan Project team to Trinity, it wasn’t just for the isolation. He had history with New Mexico, attending summer boys’ camps during his youth. Because of the popularity of the movie “Oppenheimer,” a surge of visitors is expected on October 21.

The open house event, hosted by the US Army, is free but limited to the first 5,000 guests, on a first-come, first-served basis.

How to get there

From Albuquerque International Sunport airport, your best bet is a rental car for the two-hour drive south. It’s easy to get disoriented while navigating, so stick to the Army’s directions, as GPS instructions can be wonky. Take screen photos of the route mapped on your phone – as you may lose cell service – and have an actual roadmap as backup.

Aim to arrive at Trinity’s Stallion Gate before 8 a.m., when the gate opens. There will already be a line. Be early, and you’ll still have plenty of time for the day’s second adventure. Army officials will check your ID at the gate, and from there it’s a 17-mile (27-kilometer) drive to a parking lot located a quarter-mile walk from the reason you came – Ground Zero.

Trinity Site’s atmosphere during an open house is reminiscent of a small-town carnival from a bygone era. Vendors selling souvenir trinkets. Kids in strollers. Dogs wagging tails. Porta Potties. That’s until you notice the pop-up tent displaying Geiger counters. And another with radioactive Trinitite, the mysterious green-glass rock that rained down from the bomb’s blast.

Ominous fence signs remind guests that it’s against the law to remove any pieces of Trinitite they spy on the ground because ingested fragments retain enough radioactivity to be dangerous.

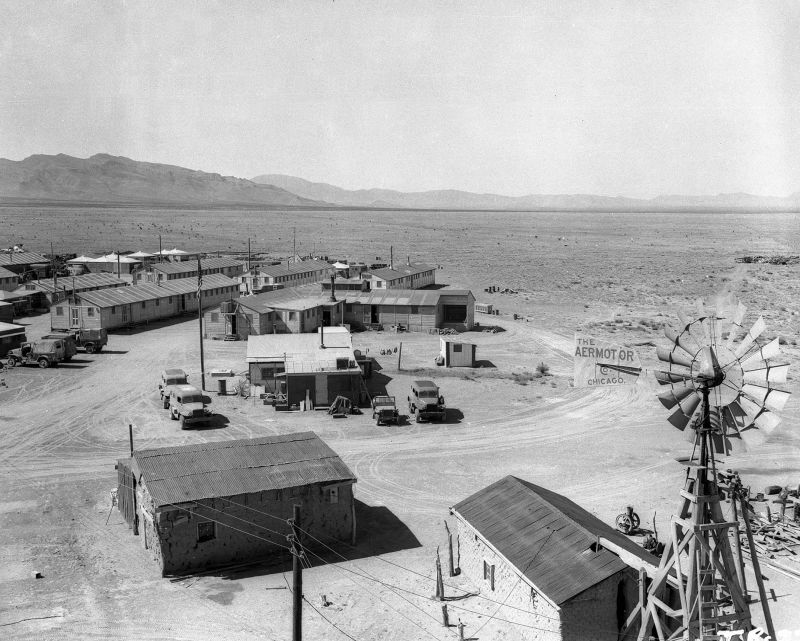

The famed 1918 McDonald adobe ranch house, where the bomb’s critical plutonium core was assembled in the master bedroom, survived the shock wave two miles away mostly intact. Buses shuttle visitors back and forth free of charge from the Trinity parking lot to the McDonald house.

Venture in farther to stand next to a life-size replica of Fat Man, the nuclear bomb dropped on Nagasaki, Japan, on August 9, 1945.

Visitors can pose for photos inside Jumbo, the 216-ton steel cylinder scientists contemplated detonating the bomb – nicknamed the Gadget – within to contain its plutonium core if the full detonation failed.

Experiencing Ground Zero

The moment arrives to approach Ground Zero, marked simply by a black stone obelisk that’s 12 feet (3.66 meters) high.

Step back in time to the pre-dawn of July 16, 1945. Glance north, west and south where Oppenheimer’s team hunkered down in three bunkers, five miles away. You stand where the course of humanity shifted. Where the boundaries of physics and possibility stretched.

Picture the 100-foot-high steel tower that stood where the obelisk stands now. A few feet away only nubs of the tower remain, the bulk annihilated in the blast.

See in your mind the mattresses hauled in and stacked high to cushion the fall should the chains snap as they winched the heavy Gadget high into the air. And young scientists rotated throughout the night babysitting the bomb as crackles of lightning threatened to strike.

Oppenheimer wrote the poem “Crossing” two decades before Trinity. His words contained the prophetic passage, “…in the dry hills down by the river, half withered, we had the hot winds against us.” He could not have imagined the heat to come.

Now close your eyes.

Ignore what you do see to imagine the history you cannot see.

The storms over the mountains. New Mexico Gov. John Dempsey is at home asleep, oblivious to when the blast will occur. Finally, the mists of rain clear. The countdown to fission begins. There’s a sense of dread, however remote, that Earth’s atmosphere might ignite in a cataclysmic chain reaction.

And finally, the detonation.

Man’s first nuclear genie shatters its bottle, unleashing the ferocity of the atom, with an explosion 10,000 times hotter than our sun. Thirty-seven minutes later, the wounded sky brightens again, to the dawn of man’s first atomic sunrise.

Reflect on the glaring omission that while the area surrounding Trinity was remote, it was not unpopulated.

Civilians termed “downwinders,” subjected to radioactive fallout fluttering down from the sky, were assured that the flash and fury some saw and heard was an ammunition explosion at nearby Alamogordo Air Base. After atomic bombs dropped over Hiroshima and Nagasaki the following month, they realized the stark truth.

Jim Eckles, an Army historian who oversaw decades of Trinity open house events, shared the site’s significance: “The ‘Oppenheimer’ movie resurrected concerns we’ve lost sight of. That thousands of nuclear warhead missiles are still out there, able to launch. We need clever intelligent people to deal with the sequence that began at Trinity.”

Journeying on to the fringes of the galaxy

After experiencing Trinity’s solemn inner journey, it’s time to regroup and explore outward — to the hope-filled fringes of the galaxy.

The world’s most impressive radio telescope – the Very Large Array – is also free of charge to October 21 guests.

Take Highway 380 back to Interstate 25 and the route to the VLA, 50 miles west of Socorro, is well-marked.

Along the way, you can stop for lunch at the same watering hole frequented by Oppenheimer’s crew, the Owl Bar & Café in San Antonio. New Mexico recently designated the sweet scent of roasted green chiles as an official state aroma, and you can savor the taste smothered on their famous Owl burgers.

Driving west past Socorro, the elevation rises. The VLA sits 7,000 feet high on the Plains of San Agustin, ringed by a fortress of mountains to block the radio interference of civilization, as astronomers search deep into the sky.

“People find the first glimpse of antennas on the sweeping desert plain awe inspiring,” said Patricia Henning, director of the VLA.

Each of the 27 colossal dishes measure 82 feet (25 meters) across and are motorized to swivel and tilt. Railroad-track mounted, they can spread out over miles in their iconic “Y” shape. According to Henning, the wider the array stretches its arms, the bigger its eye grows to zoom in.

Most people are familiar with traditional light-collecting telescopes. But the VLA collects radio waves that occur naturally from objects in space, billions of times fainter than broadcast radio waves, and then electronically transforms them into images.

It’s the most widely used radio telescope in the world, mapping the cosmos from our solar system and Milky Way galaxy to distant gas clouds and plasma ejections from supermassive black holes.

“The array studies the universe, so our main driver is not looking for intelligent life,” explained Henning. “SETI – the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence – piggybacks astronomy conducted at the VLA and then combs through copies of data looking for techno signatures.”

What’s a techno-signature? Intelligence.

As SETI scientists download the music of the universe, analyzing radio waves for signs of a composer behind the notes, you can’t help but wonder: If extraterrestrial life saw Earth’s nuclear glow, what techno-signature assessment would they make of us?

If you can’t make the October 21 open houses, don’t despair.

The VLA welcomes visitors most days, excluding major holidays. Admission is $6 for adults. And on April 6, 2024, Trinity Site again opens for a single day. Millions of colorful New Mexico wildflowers will bloom fleetingly, a contrast to Trinity’s mushroom cloud that bloomed only once but whose impact may eternally define 20th-century mankind.