El Niño is a climate pattern that originates in the Pacific Ocean along the equator and impacts weather all over the world.

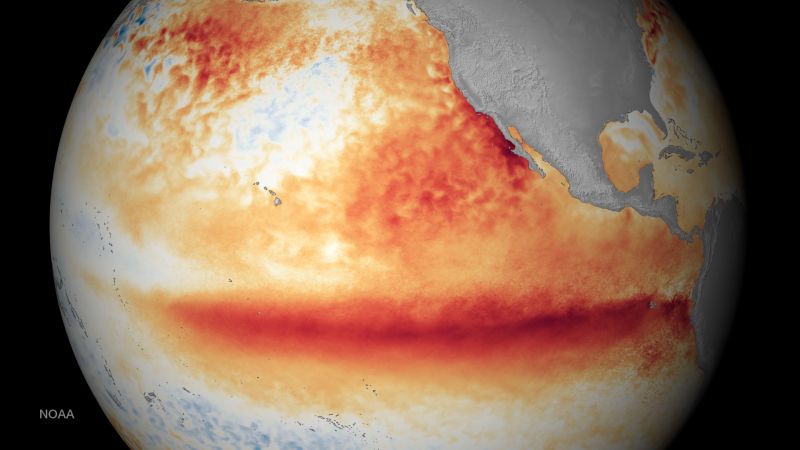

Warm water normally is confined to the western Pacific by winds that blow from east to west, pushing it toward Indonesia and Australia. But during an El Niño, the winds slow down and can even reverse direction, allowing the warmer water to spread eastward all the way to South America.

Scientists are still searching for an answer as to why this happens, but the slowing of these winds can last for weeks or months.

El Niños – among many large-scale weather patterns that act in tandem to influence global weather – occur every two to seven years in varying intensity, and the waters of the eastern Pacific can be up to 7 degrees Fahrenheit (4 degrees Celsius) warmer than usual.

El Niño, which in Spanish means “little boy,” is the opposite of the La Niña, or “little girl,” climate pattern.

El Niño offers a global study in opposites

A strong El Niño heats up the atmosphere and changes circulation patterns around the globe.

It can especially affect the jet stream – a narrow band of strong wind in the upper atmosphere – over the Pacific, which gets stronger and dumps more frequent and intense storms over the western US, especially California, and along South America’s west coast.

The atmosphere, however, is something of a zero-sum game: More rain in North and South America falls at the expense of normally rainy southern Asia and Australia, which in turn can experience droughts.

El Niño has been known to cause intense flooding across eastern sections of Africa – leading to landslides, an increase in waterborne diseases and even food shortages – while northern and southern parts of the continent experience severe drought.

A strong El Niño also influences cyclone seasons around the planet. The warmer the Pacific is, the more hurricanes or typhoons it gets – while fewer hurricanes form in Atlantic Ocean because increased upper-level winds prevent them from developing. This happened during the 2015 hurricane season, with the Pacific breaking records while the Atlantic seeing a relatively quiet year.

It can affect US rainfall – and Pacific fish

Like snowflakes, no two El Niños are exactly alike. For instance, an area of warmer water in the northern Pacific that became known as “the blob” during the 2014-2016 El Niño event wasn’t there during the 1997 El Niño.

But during typical El Niño years, more rain falls in the southwestern and southeastern United States, while the North experiences much drier and warmer weather.

And weather isn’t the only thing El Niño affects. Warmer surface waters in the eastern Pacific drive away cold-water fish that are the backbone of the fishing industry in much of Latin America. In fact, fishermen there first noticed the phenomenon and named it “little boy” or “Christ child” in Spanish, since it often appeared around Christmas.

Its climate crisis impact is under review

The influence of the climate crisis on El Niño is still a matter of debate.

Climate change could make El Niños’ impact worse, some recent studies show. And while the overall number of El Niños is unlikely to increase as the planet warms, amplified, so-called “super” El Niños will be twice as likely, other research suggests.

Among the most likely byproducts of global warming are more extreme precipitation events because warmer temperatures can hold more water vapor in the atmosphere. That could make El Niño-induced floods even more devastating.